THE MOST EXOTIC PHENOMENA OF QUANTUM FIELDS

- planck

- Aug 9, 2025

- 6 min read

In addition to the best-known and most studied phenomena, the Standard Model of particle physics includes some rather more "exotic" and lesser-known effects. These effects, called nonperturbative effects, have surprising properties and are often based on an aspect of nature that has only recently been deeply studied: topology. Although topological effects were not considered in many early studies of quantum fields, it has been shown that in many systems their effects are of central importance in both quantum mechanics (QFT) and general relativity. These effects reveal a hidden but fundamental aspect of nature and lead us through the most exotic and surprising physical phenomena. In this article, we will discover some of these incredible phenomena.

Non-trivial geometries

Imagine we arrive at a small planet with a perimeter of a few hundred kilometers and want to know (without exploring it directly) whether it is spherical or doughnut-shaped. Imagine we have a device capable of rapidly deploying a string in all directions, capable of spanning the entire surface of the planet. We can then activate our device from any position and retract the string again to retrieve it. If it is possible to retract and store the string in the device, then we are on a sphere; if the string gets stuck and we cannot retract it, then we are on a toroidal planet (a doughnut). Spaces of the first kind are called simply connected spaces or spaces with trivial topology; those of the second kind are called spaces with non-trivial topology. To transform a trivial space into a non-trivial one, it would be enough to remove any single point: now it is no longer possible to contract the string, since it would remain stuck in the position occupied by that point. This is what we will attempt to do in the next section.

Dirac strings

Next, we will remove a point (or rather a line) from our space (1)

You might be wondering: How can something like this make sense?

Let's consider a space free of any physical interaction; this space is completely symmetrical: there are no privileged coordinates or directions. Next, we introduce into our space a very long (ideally infinite) solenoid through which an electric current flows. The solenoid extends along the negative side of the z axis:

Let S be the solenoid cross-section, and "landa" be the current per unit length. The solenoid's magnetic field can be considered the sum of a large number of small magnetic dipoles dm. The magnetic dipole between a length z and a length z+dz will be:

The magnetic dipole at the point z=0 creates a potential:

Therefore the total potential will be:

The potential is singular (infinite) for just two angles: 0 and PI. These two angles therefore describe a straight line where the potential is undefined. This straight line is called the Dirac string and, from a theoretical point of view, is a singular object.

From the perspective of the potential, we can perform any calculation at any point outside the line. It's as if it were necessary to remove the line for the potential to make sense. If this line is (ideally) infinite, our initial space becomes "broken" or "unconnected," so that our trivial space has become a space with nontrivial topology or a space with topological charge.

Topological loads

At the point z=0 on our z-axis from the previous section, we have a magnetic charge of (Lambda*S/c), which is the charge attributed to a magnetic monopole (see this article ). This is why magnetic monopoles, whose existence is predicted by our fundamental theories, are related to topological charges.

Next, we'll do something a little unusual: we'll take our magnetic charge (our magnetic monopole) and move it along a closed path. Let's suppose we have a device that measures the work done in moving the magnetic charge. In the absence of external fields, the meter doesn't change its reading. Next, similar to the previous section, we'll transform the "topological configuration" of our space. To do this, we introduce a closed electric circuit C2 that creates an electromagnetic field:

Next, we pass close to circuit C2, but the meter remains unaffected. What happens? We eventually cross surface C2, and the meter increases by one position (representing a fixed amount of work done). No matter what path we take, how far we travel, or how close we are to C2 , the meter will only count the times we cross surface C2 and will always increase by a fixed number!

The number of times the monopole (along with its Dirac string) crosses the surface S is called the "winding number." This number is a topological invariant and, as we will see, plays a very important role in the Standard Model.

The infinite voids of the standard model

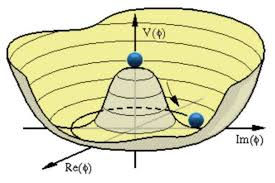

When the energy of our Universe dropped below 246 GeV, a spontaneous symmetry breaking mediated by the Higgs field occurred. At that moment, the field potential dropped from the peak to any point on the circle of minimum energy:

This randomly chosen point is not unique; in fact, gauge symmetry implies that I can choose any other point on the circle since they are physically equivalent. This means that there isn't just one vacuum in the theory, but rather infinitely many possible vacuums. This can be represented as follows:

However, when we include possible topological effects in our theory, a subtle, exotic phenomenon emerges: different vacuums can have different winding numbers, that is, different topological charges. This is because the characteristics of the vacuum are determined by the phase of the Higgs field. This phase, being complex, can be any multiple of 2PI; that is, the complex phase can have completed any number of complete turns and therefore can have any winding number at different points in the vacuum state. Therefore, we find that we have an infinite set of vacuum states with different topological charges.

Instants

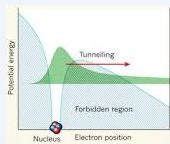

In this section, we reach the more "exotic" entities of the SM. As we know from the principles of quantum mechanics, a particle trapped in a potential has a nonzero probability of escaping through the tunneling effect. In the case of the infinitely many SM vacua, there is a probability that the vacuum will "jump" from one value to another through the tunneling effect. This probability is given by entities called instantons:

The probability of a particle tunneling from one potential minimum to another is given by an instanton. The probability of the reverse jump is given by an anti-instanton.

Instantons are solutions to the Lagrangian equations and are so named because the transition occurs in a brief instant of time. Instantons represent a kind of quantum tunneling between two classically disconnected states:

These entities have another "exotic" characteristic: the instant at which the "jump" occurs, its probability, and its topological properties are calculated in complex time , that is, in Euclidean space-time. This complex space-time seems to play a fundamental role in describing the quantum tunneling effect; in fact, there are theoretical models to describe the emergence of our Universe by tunneling through a "bubble of nothing," that is, a bubble in Euclidean space-time.

Instants and confinement

One of the most important unsolved problems in the MS is explaining the phenomenon of confinement, that is, explaining the specific physical mechanism that keeps quarks bound within the atomic nucleus. The atomic nucleus is a complex place where seas of quarks, antiquarks, gluons, and instantons are "compressed."

Although the confinement phenomenon is not yet fully understood, the general idea of how it can work is quite similar to what happens in a superconductor: when a critical energy value is crossed, a spontaneous symmetry breaking occurs, the electrons (spin 1/2) form bound states and behave like bosons (spin 1) that do not respect Fermi statistics and flow without resistance through a narrow zone of the conductor.

Inside the atomic nucleus the image would be quite similar:

- Two light fermions are separated by a bell-shaped potential like the one in the previous figure. Instanton-antiinstanton pairs begin to emerge across the potential barrier:

- This exchange of particles produces an attraction that causes the quarks to form bound states. Analogous to Cooper pairs in a superconductor, these bound pairs behave like bosons that form a quark condensate.

- This quark condensate then causes the vacuum state to behave like a superconductor: the gluon field is expelled except in a narrow, cylinder-shaped region between a quark and an antiquark. In this region, the potential is attractive (due to the gluons) and its value increases linearly with the separation between the quarks, i.e., it behaves like a kind of string holding the quarks together. This explains the force that holds all matter in the Universe together!

In this image of confinement, the quantum tunneling effect and instantons play a fundamental role. Instantons may explain why all the matter we see in the Universe exists!

Grades:

(1) By "space" we mean the mathematical "space" that contains the gauge fields

Sources:

Comments