TAMING THE SPEED OF LIGHT

- planck

- Jul 24, 2025

- 6 min read

All known matter is made up of particles called fermions (electrons and quarks). On a macroscopic scale, we see well-defined solid bodies; however, on the natural scale where these particles "live," the world is completely different, so much so that it seems incredible that our everyday world could emerge from this strange, ever-changing world.

In this article, we'll focus on the most famous fermion of all: the electron. The electron will reveal its internal degrees of freedom, where it appears to move at the speed of light, multiple faces, strange "superimposed" behaviors, entangled states, and a kind of strange spin that bears no resemblance to anything we know in our macroscopic world. Furthermore, the electron carries additional "hidden" information distinct from the "usual" physical quantities.

Welcome to the strange world of fundamental particles!

Taming the speed of light: the mass of the electron

The photon, traveling at the speed of light, always moves in a straight line in one of the spatial dimensions. From this point of view, we can say that the photon "senses" only one dimension (1).

The photon must move in a straight line (gray arrow) at speed c, which is the maximum speed allowed, so it cannot have any spin component in the direction of movement. If it did, the total speed would be greater than ac (which would happen with the red arrow in the drawing).

Let us consider the equations for two plane waves traveling at the speed of light in opposite directions, one to the right and one to the left:

The first term represents the energy, and the second the momentum of the wave. If we shift the second term to the right, the equations tell us that all the wave's energy is concentrated in the momentum due to the wave's displacement to the right (case 1) or to the left (case 2). If we square either of these equations, we unify both equations into one:

The problem with the above equation is that it is neither quantum nor relativistic. The first problem is solved simply by replacing the expressions for E and p with the equivalent quantum operators: E=ihd/dt and p=-ihd/dx and the second by applying the relativistic expression for energy and momentum: E2=m2c4+c2p2. Substituting the two operators into this last expression, we obtain:

Although it may not seem so at first glance, this last expression represents a change of great significance. Previously, all the energy of the wave was concentrated at the moment of the wave, now a new term has emerged that also has energy: the mass of the particle. We have given the wave mass! Furthermore, by transforming our classical wave into a quantum-relativistic wave, we have achieved something astonishing: we have coupled the two waves traveling in opposite directions: the latter

This equation has two solutions that represent the motion of two waves traveling in opposite directions and that behave as if they were "mixed," or rather, superimposed. The wave function is no longer an "individual" wave; it is a "mixture" of two waves. But what physical interpretation should we give to the "superimposed" equation above? To get an intuitive (classical) idea, we can consider the following system of coupled springs and masses:

In this system, the ball moves to the right (or left) like a wave, but due to the vertical springs, the "wave" slows down, stops, and reverses its motion, moving in the opposite direction, repeating the cycle over and over again. The horizontal springs act as a coupling between the two waves, and the vertical springs represent a new degree of freedom: mass. By coupling the two waves , the coupled assembly acquires mass!

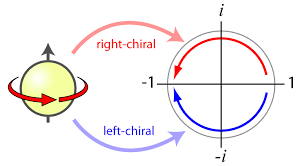

Mass represents a new degree of freedom that massless particles traveling at the speed of light do not have. Now the system can rotate in the direction of the displacement: the two chiral components "reflect" or "spin" transforming into each other. This continuous "reflection" or "spin" between the chiral components determines a direction in space-time; this direction is spin (2). In this way,

In this way, through the quantum-relativistic equation we have managed to "tame" the speed of light and give the particle mass (3)

The continuous "reflection" of coupled waves

The above "superimposed" equation (called the Klein-Gordon equation) has two solutions: ei(Et+px) and ei(Et-px). These solutions represent a merging, or rather, a superposition , of two waves moving in the complex plane: the real part of one of them is "reflected" and becomes the imaginary part of the other, and vice versa. This continuous "reflection" or "spin" can be seen more clearly in the following diagram (4):

It is now that we begin to appreciate the intricate relationship between the physical world and the world of mathematics: the two coupled waves move in a complex mathematical space. The appearance of complex numbers is another way of representing "superimposed" numbers; two complex numbers actually represent four numbers: two real and two imaginary. There is another way to express this fusion of two expressions, and that is to use, instead of just two numbers, a "box" with four numbers. This "box" with four numbers is called a 2x2 matrix:

This mathematical expression is equivalent to our first "superimposed" equation. It more clearly shows the "mixing" or "superposition" of the values in both the wave function and the energy and momentum of the wave. To calculate the true velocity of the particle (the electron), we must apply the velocity operator.

Considering that this acts on the wave function and the chiral components of the particle, we obtain the velocity of the entire set (the electron's actual velocity):

The mysterious "spin" of the particles that make up matter

Now things get even stranger and more interesting: we're going to rotate our electron 180°. This can be done in experiments because spin is actually the electron's magnetic moment, so we can modify the moment by applying an external magnetic field. Let's see what happens:

1st) 180º turn

If we perform the spin by reversing the direction of motion of the electron (turning the spin direction 180º) we obtain that the direction of spin of the electron has been reversed and therefore we go from an electron with spin up to one with spin down (or vice versa). If we then carry out interference experiments of these electrons with non-spinning electrons , both electrons do not interact! If instead of reversing the direction of motion of the electron, what we do is spin the electron while keeping its direction of motion (its spin direction) unchanged , we obtain the same effect!

By rotating the electron 180º we reverse its direction of rotation and its movement and therefore also its spin direction.

2nd 360º Turn

Now we come across the most counterintuitive and paradoxical effect: if we rotate the electron 360º we would obviously expect to obtain the original electron, however, when we do so and perform interference experiments with unrotated electrons what we have is that both electrons interfere negatively!

3rd 720º Turn

If we spin our original electron 2 full turns, then we get our initial electron! That is, a 720º spin is necessary to restore the original properties of our particle. The world of the electron is very different from ours! As if all this were not "strange" enough, the electron has the remarkable property of detecting any angle of spin on any axis with respect to its original angle (in this article we have limited ourselves to only 2 dimensions for simplicity, but the results are equivalent in 4 dimensions). This angle is called the electron's spin phase. This teaches us another fascinating property about the electron, and about leptons in general: they carry more information than a simple three-dimensional vector (magnitude and direction); they also carry additional information: the spin phase angle.

Conclusions

Relativity requires that all observers, regardless of their state of motion, must measure the same fundamental physical quantities (relativistic invariants). For this to be possible, nature must "split" the electron.

into two chiral components and "create" a kind of spin that produces an intrinsic magnetic moment (the spin). On the other hand, quantum mechanics implies the existence of a wave function that contains all possible measurement outcomes.

(spin up and spin down in the case of spin). When the two chiral components are coupled, interference occurs between them, suppressing their propagation in the light cone. In this way, the wave function remains located outside the light cone (in the context of the holographic principle, we would say that it remains in the "bulk," which has an additional dimension), moving at speeds less than c. From a quantum perspective, the electron is actually a perturbation of the electronic quantum field; this perturbation is then a quantum superposition of all possible values, continuously "oscillating" such that all observers measure the same relativistic invariants. Nature is undoubtedly absolutely amazing.

Grades

(1) The photon actually has two degrees of freedom, which are composed of its two different polarizations. These polarizations are always orthogonal to the direction of motion, so the speed of light is never exceeded.

(2) Spin, along with all other electron properties discussed in this article, are quantum properties with no classical analogue, so any classical analogy is only an approximation.

(3) In the quantum process in which the mass of the electron is generated, the Higgs field also intervenes, which "mixes" both chiral components.

(4) The electron is a fundamental particle that cannot be broken down into more elementary components. The fact that the electron "oscillates" between its two chiral components does not mean that it is made up of more fundamental elements.

PS 05-31-2017: In response to Jarenito's questions in the comments, I have added a clarifying figure:

The two chiral components "reflect" or "rotate" perpendicular to the direction of motion that coincides with the overall spin direction of the particle (gray arrow).

Sources: The relativistic Dirac equation

Comments